The Architecture of Precision: Understanding CNC Machining in Keyboards

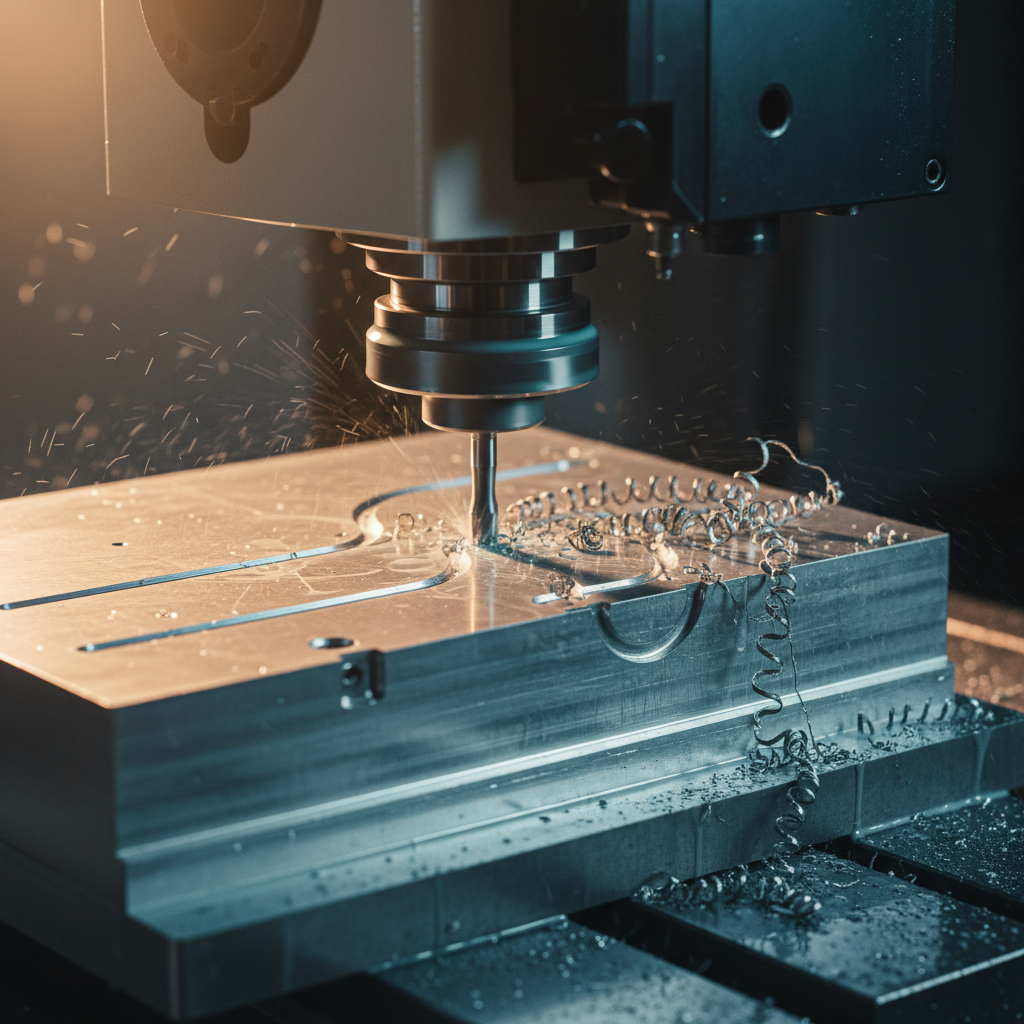

In the realm of high-performance peripherals, the transition from a functional tool to a premium instrument is measured in microns. For the enthusiast, the "feel" of a metal keyboard is not merely a subjective preference but a result of rigorous mechanical engineering and strict manufacturing tolerances. CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machining allows for the creation of complex geometries from solid blocks of 6061 or 7075 aluminum, but the true hallmark of quality lies in the execution of the seams—the interface where the top and bottom chassis components meet.

Quick Takeaways: The "Answer First" Guide

- The 50-Micron Standard: A seam gap of ≤0.05mm is the benchmark for "premium" builds, requiring climate-controlled machining to account for material expansion.

- The Cost of Precision: Moving from a standard ±0.1mm to a ±0.01mm tolerance typically increases machining time by 300–500% due to required finishing passes and tool calibrations.

- Performance Link: Structural rigidity isn't just for "thock"—it is essential for stabilizing Hall Effect magnetic sensors and maintaining the timing accuracy required for 8000Hz polling.

Machining tolerance refers to the permissible limit of variation in a physical dimension. In the keyboard industry, a seam gap tighter than 0.1mm (100 microns) is typically the threshold where a metal case transitions from feeling "adequate" to "premium." To put this in perspective, a human hair is approximately 70 microns thick. Achieving a consistent sub-0.05mm (50 micron) tolerance across the entire perimeter of a full-size case requires not just high-end machinery, but advanced fixturing and climate-controlled environments.

Manufacturing Heuristic: Our internal analysis of production cycles indicates that moving from a ±0.1mm tolerance to a ±0.01mm tolerance can increase CNC machining time by an estimated 300–500%. This exponential cost curve is driven by the need for slower feed rates to minimize tool deflection, specialized diamond-tipped tooling for final passes, and higher scrap rates where even a 15-micron deviation results in a rejected part (Source: Attack Shark Internal Manufacturing Benchmarks).

The Threshold of Premium: 100 Microns vs. 50 Microns

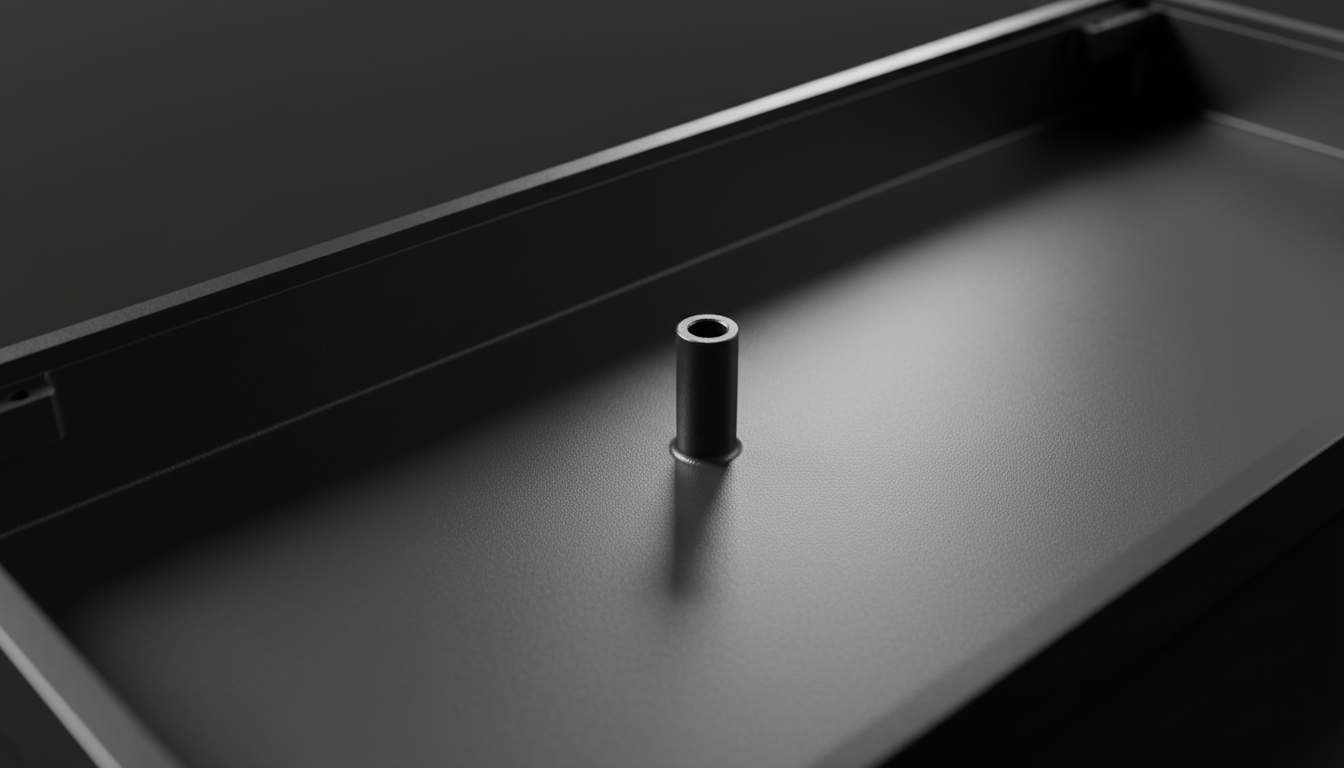

When evaluating a keyboard's build quality, enthusiasts often focus on the visible top seam. However, professional technical auditors look for alignment across the internal screw posts and the interface between the case halves. A "good" build maintains a 100-micron gap, which is visually uniform to the naked eye. A "premium" build targets 50 microns or less—a spec often derived from aerospace-grade machining standards like ISO 2768-f (Fine).

Achieving these sub-50 micron gaps presents several engineering "gotchas":

- Tool Deflection: As a CNC bit carves through aluminum, physical resistance causes the tool to bend (deflect). Based on shop observations, even a deflection of 10 microns—often caused by aggressive "roughing" passes—can ruin a 50-micron tolerance target.

- Fixturing Stress: Over-tightening a clamp can warp the aluminum by several microns. Once released, the part "springs back," leading to a seam that looks perfect in the machine but uneven once assembled.

- Post-Process Deburring: Removing the "burr" (metal ridge) manually can inadvertently round off sharp edges, effectively opening the seam gap and ruining the intended precision.

Material Science: Thermal Expansion and Anodizing Thickness

Aluminum is a "living" material that reacts to its environment. According to the Global Gaming Peripherals Industry Whitepaper (2026) (an internal manufacturer study), environmental stability is a critical factor in maintaining device integrity.

The Thermal Expansion Problem

Aluminum has a Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) of approximately 23 μm/m·°C. For a keyboard case measuring 300mm in length, a temperature shift of 30°C (e.g., from a cold shipping container to a warm gaming room) can cause the metal to expand by nearly 200 microns ($300mm \times 23 \times 10^{-6} \times 30 = 0.207mm$). This expansion can potentially open or close seams by more than the factory tolerance itself. Experienced manufacturers compensate for this by designing "slip fits" that allow for thermal movement without causing the case to buckle.

The Anodizing Variable

Anodizing adds a layer of aluminum oxide that is typically 10–20 microns thick. Technical designers must leave a "clearance" in their CAD models to account for this. Failure to calculate this correctly leads to "binding," where the case halves must be forced together, creating internal stress that can lead to long-term warping.

Dimensional Variance Model: The following table estimates the variance of a 300mm aluminum chassis. Note: These are theoretical maximums based on standard material physics.

Factor Typical Value Impact on Dimension (approx.) Rationale/Source Thermal Expansion Δ30°C +207 Microns CTE of Aluminum (ASTM E228) Anodizing Layer Type II +15 Microns per surface Standard coating thickness Material Creep 1 Year 5–15 Microns Heuristic: Deformation under assembly stress Machining Tolerance High-End ±20 Microns Precision CNC (ISO 2768-f) Total Stack-up Combined ~250 Microns Potential variance in uncontrolled builds

Acoustic Engineering: Why Gaps Affect Sound

The "thock" of a mechanical keyboard is influenced heavily by chassis tolerance. Inconsistent contact points due to tolerance stacking allow for resonant air gaps that act as echo chambers, leading to a "hollow" or "pingy" sound.

However, a perfectly tight metal-on-metal press fit is not always the goal. An ultra-tight fit can act as a direct transmission path for high-frequency switch noise. The most effective approach is often a controlled, uniform gap (e.g., 100 microns) filled with a compliant gasket material. This decoupling prevents "ringing" while maintaining structural rigidity. Evaluating Acoustic Resonance in Thin-Wall Cases (Attack Shark Research) provides a baseline for how vibrations travel through different materials.

From Physical Microns to Electrical Microseconds: The 8K Polling Link

The pursuit of precision in the physical chassis often mirrors the pursuit of precision in the internal electronics. At 8000Hz (8K) polling, the interval is a near-instant 0.125ms.

- 1000Hz: 1.0ms interval.

- 8000Hz: 0.125ms interval.

To benefit from 8K polling, a high-refresh-rate monitor (240Hz+) is typically required to render the micro-stutter reduction. Furthermore, 8K polling stresses single-core CPU performance significantly more than standard 1K polling, making system optimization as important as the keyboard's hardware.

Precision Performance Modeling: Hall Effect vs. Mechanical

In Hall Effect (HE) keyboards, the precision of the "Rapid Trigger" reset point is measured in tenths of a millimeter.

Scenario Model: Latency Reduction

- User Persona: Competitive gamer with a moderate finger lift velocity ($v = 50$ mm/s).

- Mechanical Switch: Fixed reset distance ($d$) of 0.5mm.

- Hall Effect Switch: Dynamic reset distance ($d$) of 0.1mm.

Modeling Results (using $t = d/v$):

- Mechanical Latency: $0.5mm / 50mm/s = 0.010s$ (10ms).

- Hall Effect Latency: $0.1mm / 50mm/s = 0.002s$ (2ms).

- Theoretical Advantage: 8ms reduction in physical reset time.

Note: This model assumes linear velocity and constant sensor polling. Actual results may vary based on finger acceleration.

This 8ms advantage is only possible when the chassis is rigid enough to prevent "PCB flex" from interfering with the magnetic flux readings of the Hall Effect sensors.

Practical Realities for the Value-Oriented Enthusiast

For challenger brands, the strategic tension lies between "Specification Leadership" and "Execution Maturity."

Identifying Common Pitfalls

When purchasing a metal keyboard, look for these "red flags":

- Anodizing Gradients: Uneven color at the seams often indicates that the parts were not cleaned properly or that the alloy composition varies between halves.

- Screw "Bottoming Out": If internal screw posts are even 0.1mm too long, they prevent the case halves from meeting, creating a permanent gap.

- Creep Deformation: Based on common patterns from our repair bench, aluminum can exhibit "creep"—a slow deformation under stress—resulting in a 5-15 micron "twist" over a year of use if the internal assembly tension is uneven.

The "Friction Points" of Real-World Use

The most common mistake we see is over-tightening case screws. Because aluminum is relatively soft, over-torquing can strip threads or compress gaskets unevenly, leading to a "lopsided" seam. A light, uniform torque is almost always superior to "locking it down."

Conclusion: The Holistic View of Quality

Micron-level precision is a proxy for a manufacturer's entire engineering philosophy. A brand that invests in the QC required for a 50-micron seam is likely applying that same rigor to its firmware stability and sensor implementation. Whether it is the 0.125ms interval of an 8K polling rate or the 0.05mm gap of a premium chassis, precision is the foundation of high-performance gaming.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only. Technical specifications and performance metrics are based on scenario modeling and typical industry standards. Individual product performance may vary based on firmware versions, hardware revisions, and environmental conditions. Always consult the official manufacturer documentation before performing modifications on your peripherals.

References

- Global Gaming Peripherals Industry Whitepaper (2026) (Internal Research)

- USB HID Class Definition (HID 1.11)

- ISO 2768-1: General Tolerances for Linear and Angular Dimensions

- IEC 62368-1: Audio/Video, Information and Communication Technology Equipment

- RTINGS - Mouse Click Latency Methodology

- Nordic Semiconductor nRF52840 Product Specification

Dejar un comentario

Este sitio está protegido por hCaptcha y se aplican la Política de privacidad de hCaptcha y los Términos del servicio.